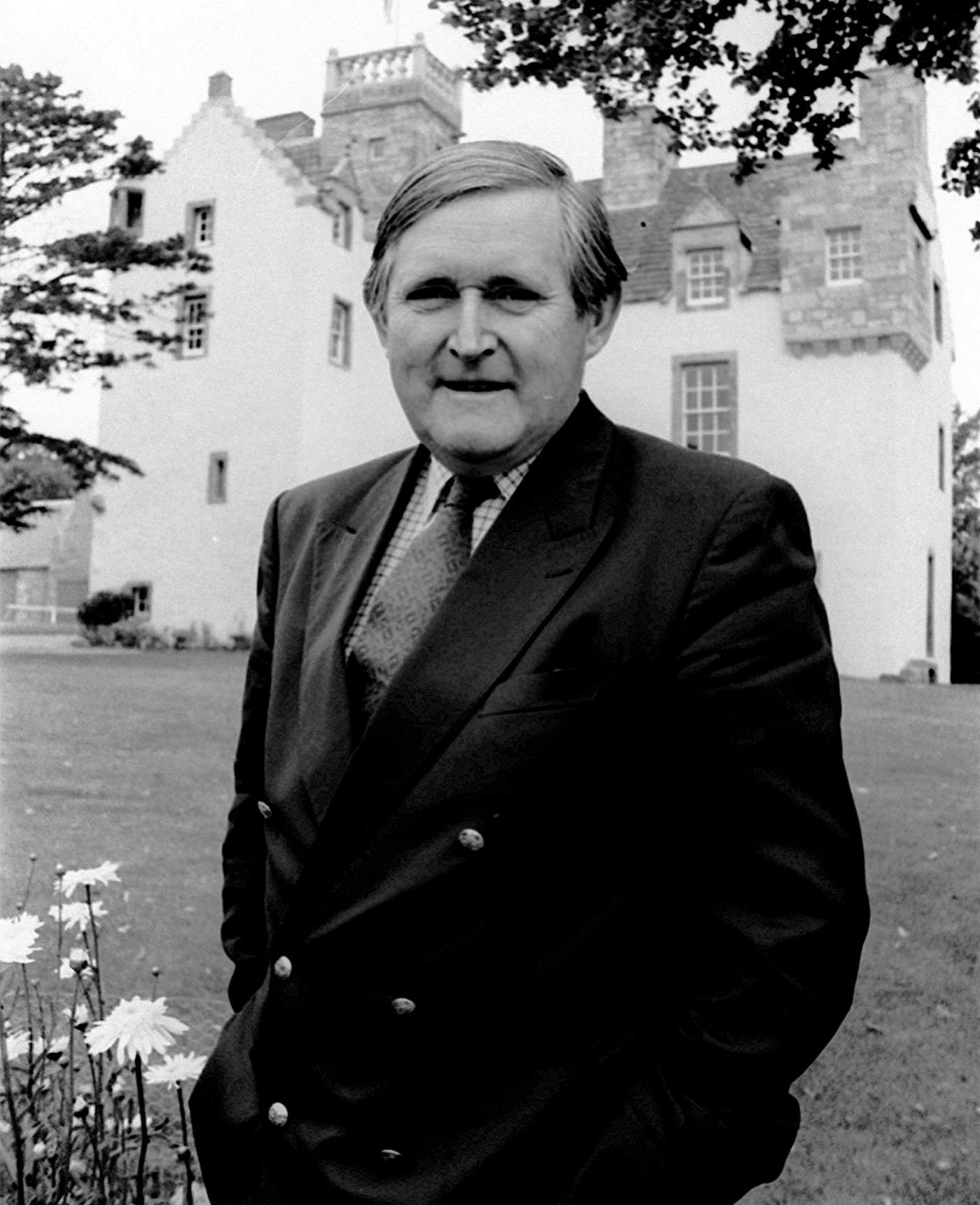

Sir Angus Grossart, merchant banker and patron of the arts, was for more than half a century an irresistible force in Scottish public life.

He described himself, half in jest, as a member of the “Scotia Nostra”, a man who wielded great influence: first through Noble Grossart, the boutique investment bank active in several epic UK takeover battles in the 1980s, including the “whisky wars” involving Guinness and Distillers.

The banker was a ubiquitous string-puller in the cultural world. He chaired or squatted on the board of all the major museums and galleries in Scotland, chaired a private auction house (Lyon & Turnbull), and contributed to numerous philanthropic causes. “Angus was a Renaissance man,” said Sir Ewan Brown, his long-time partner at Noble Grossart, “but he was also a street fighter when required.”

One of three sons of a Lanarkshire tailor, Grossart, who has died aged 85, claimed his first business experience was selling reject factory toffee on a street stall. A junior golfing champion, he studied law at Glasgow University but soon found the bar to be “a little cloistered”.

In 1969, he co-founded Noble Grossart with Sir Iain Noble, a Scottish landowner and Gaelic language activist. Noble soon left with a half-a-million-pound buyout, but Angus retained the name, turning an initial £30,000 investment into well over £300mn

During the 1970s, the bank prospered through word of mouth and patient growth, driven partly by the discovery of North Sea oil, which revived animal spirits in Scotland. Grossart took a lucrative stake in the Wood Group, the oil services firm, and backed entrepreneurs such as Kwik-Fit’s Sir Tom Farmer, Stagecoach’s Sir Brian Souter and banker Benny Higgins.

Grossart never met a title he did not like, a source of trouble in 2018 when he accepted the Medal of Pushkin for services to the arts from Vladimir Putin. He reluctantly agreed to hand it back after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

As someone who loved dressing up, his great regret was that, though awarded a knighthood, he failed to make the Order of the Thistle — the equivalent in chivalry of England’s Order of the Garter. The explanation probably lies in the sorry saga of the Royal Bank of Scotland.

In 1981, when I first met him as a cub reporter on the Scotsman, Grossart led opposition to the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank’s takeover of the Royal Bank. The “backwoodsman” (and they were all men) saw off the bid, arguing it would turn Scotland into a branch economy of the UK.

Two decades later, the Royal Bank launched an audacious takeover of the larger NatWest bank. There followed breakneck growth under Fred “The Shred” Goodwin and the calamitous implosion of RBS in the 2008 global financial crisis. Grossart, vice-chair, got out just in time in 2005, but like a generation of Scottish businessmen who packed the RBS board, his hard-earned reputation for prudence never quite recovered.

Noble Grossart’s heyday was over, a victim of both Big Bang deregulation which favoured capital-rich international investment banks and Grossart’s reluctance to offer equity to high-performing employees. His parsimony was legendary. “At the end of the RBS board meeting, Angus would help himself to two Havana cigars, in addition to the one he was smoking,” recalled Sir George Mathewson, former chief executive and chairman.

But his generosity of spirit was notable, too. He was passionate about Scottish culture and history, from Sir Walter Scott to the Glasgow aesthetic movement, populating his private collection at home in Edinburgh and at Pitcullo Castle, a restored rural retreat in Fife.

Sir Jonathan Mills, former director of the Edinburgh Festival, said Grossart skilfully combined business acumen with an eye for the visual arts and a deep knowledge of his subject. His greatest triumph was perhaps as head of the Burrell Renaissance in Glasgow. He donated £1mn to a £66mn restoration of the eponymous museum and successfully pleaded for a change in the will (and the law), allowing the former Scottish shipping tycoon’s eclectic private collection to tour abroad.

This was Scotland in his own image: confident, outward-looking and determined to leverage its heritage. He celebrated this tradition in Gleneagles every December at “Scotland International”, a private gathering of 60 prominent figures from academia, the arts, business and the odd retired spy. Politicians were not welcome. “I belong to two parties,” he liked to say, “the Grossart party and the dinner party.”

Grossart never spoke on the vexed question of Scottish independence or the SNP’s record in power, but privately bemoaned the stifling of initiative and the “conspicuous” absence of non-political voices in contemporary Scotland. “Many follow, few lead,” he concluded, wistfully.