A lot was happening in markets when Covid-19 shut down the world in March 2020. One of the most noted happenings was how the price of many fixed-income ETFs became unmoored from the value of the bonds they contained.

It seemed like vindication for people like Carl Icahn and Michael Burry, who had warned that ETFs had become so big that they were dangerous — especially in less traded markets like bonds. Finally, the illusory liquidity of the ETFs had collided with the harsh reality of the illiquid assets they held!

However, an interesting paper from Anna Helmke of the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School takes the other side, arguing that ETFs are actually a better fit for illiquid asset classes.

ETFs may be more suited for less liquid index market segments favored by long-term investors, whereas MFs may be a better fit in liquid fund market segments favored by investors with short-term liquidity needs, such as money market funds. Both funds are virtually perfect substitutes in highly liquid market segments, such as large-cap domestic equities.

Full disclosure: I am particularly keen on this paper because it corroborates something that has been my cautious view since at least April 2020. And despite the often -cough- robust feedback since then, I’ve become increasingly convinced this is right.

Here’s the basic argument: Traditional mutual funds guarantee investors that they will be able to redeem their money in cash at the fund’s end-of-day net asset value — the NAV. Most of the time that works fine, and as Helmke points out, that commitment is quite valuable to a lot of investors that don’t need intraday liquidity.

But in times of serious stress, bond market liquidity often gums up. Bond funds therefore tend to sell their best, most liquid bonds first to meet a rush of redemptions (because these will sell at the lowest discount). That leaves a less liquid, junkier fund for the investors who remain.

That’s obviously not attractive, so there’s an inherent bank-run dynamic at play. Investors have a strong incentive to get out as fast as possible to avoid getting penalised financially — or in extremis getting stuck if the fund depletes all its easily sellable assets and is forced to gate. As the IMF said in 2022:

Investors can sell shares daily at a price set at the end of each trading session, but it may take fund managers several days to sell assets to meet these redemptions, especially when financial markets are volatile.

Such liquidity mismatch can be a big problem for fund managers during periods of outflows because the price paid to investors may not fully reflect all trading costs associated with the assets they sold. Instead, the remaining investors bear those costs, creating an incentive for redeeming shares before others do, which may lead to outflow pressures if market sentiment dims.

Pressures from these investor runs could force funds to sell assets quickly, which would further depress valuations. That in turn would amplify the impact of the initial shock and potentially undermine the stability of the financial system.

In contrast, ETFs trade like shares on an exchange. In the background, their shares are being constantly created and redeemed by specialist ETF market-makers known as “authorised participants” to match supply and demand. Because if the stock price drifts away from the value of the bonds the ETF contain, it opens up a lucrative arbitrage for APs.

When the ETF price is higher than the NAV they can buy bonds that match the index and exchange them for new shares in the ETF. If the price falls below the NAV of the underlying bonds, they can redeem the shares for a basket of the underlying bonds and then sell them. Most of the time this arbitrage keeps ETFs closely tied to their indices.

However, when the bond market freezes, the arbitrage breaks down. APs can’t sell the bonds. So they slow or stop redeeming shares in kind, even when the price of the freely-traded ETFs shares and the NAV diverge.

And in March 2020 the dislocation was wild, as you can see below:

However, this is a good thing.

In essence, the secondary market trading of ETF shares acts almost like a pressure release valve when the underlying bond market seizes up. At a time when you couldn’t sell a swath of the fixed income markets, even at the peak of the turmoil, investors who needed to raise cash in a hurry could always ditch bond ETF shares. The NAVs were stale and misleading, because of the lack of underlying trading, while ETFs plummeted in value.

But most importantly — from a systemic risk point of view at least — the incentives are better than they are for traditional bond mutual funds. With ETFs, exiting investors are penalised (they sell at the discounted market price, not the NAV). With bond funds, remaining investors are penalised (because they are usually stuck in a junkier less liquid vehicle).

One deters investor runs, the other encourages them. The clear corollary is that ETFs may actually be the better structure for less liquid asset classes like bonds, which goes against what many people have been arguing over the past decade (including me, at least before 2020).

As Helmke writes:

. . . ETFs’ market-based pricing mechanism gives rise to reverse run incentives, as strategic substitutabilities encourage shareholders to remain invested when intermediaries are balance sheet constrained. Investors who do not need immediate access to liquidity will always abstain from selling their ETF shares prematurely. The opposite is true for MFs. The insufficient flexibility of MF prices leads to payoff complementarities, encouraging early redemptions by long-term investors during periods of market illiquidity, potentially culminating in mutual fund runs.

A lot of people will howl that only the Federal Reserve’s remarkably aggressive interventions — including a vow to buy corporate bond ETFs — helped prevent a far worse disaster for ETFs.

And sure, yes, if the Fed had just sat on its hands then things would have been far worse. But we were closer to mass gating across the bond mutual fund complex than we were to a serious bond ETF accident.

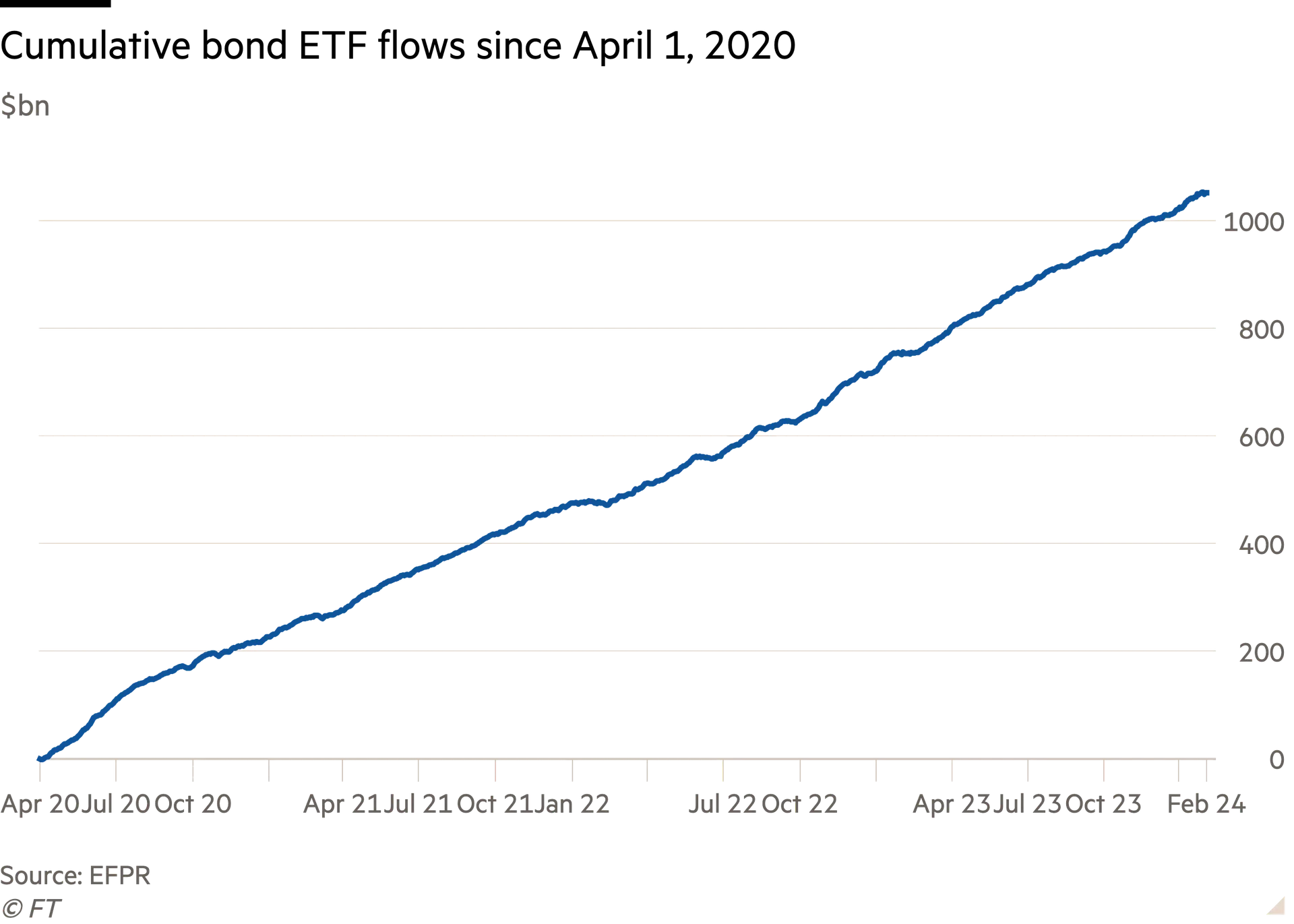

This is why, despite one of the biggest fixed income bear markets in centuries, bond ETFs have seen net inflows of over $1tn since April 2020.

The downsides of end-of-day NAV redemptions for mutual funds are also why the SEC in 2022 proposed to introduce swing pricing to mutual funds, which would pass on the transaction costs of redemptions to exiting investors As chair Gary Gensler said at the time:

A defining feature of open-end funds is the ability for shareholders to redeem their shares daily, in both normal times and times of stress. Open-end funds, though, have an underlying structural liquidity mismatch. This can raise issues for investor protection, our capital markets, and the broader economy. We saw such systemic issues during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, when many investors sought to redeem their investments from open-end funds. Today’s proposal addresses these investor protection and resiliency challenges.

Swing pricing was shouted down by the asset management industry last year.