One of the oldest and best-known hedge fund strategies has suffered nearly $150bn in client withdrawals over the past five years, as investors tire of their inability to capitalise on bull markets or protect them during downturns.

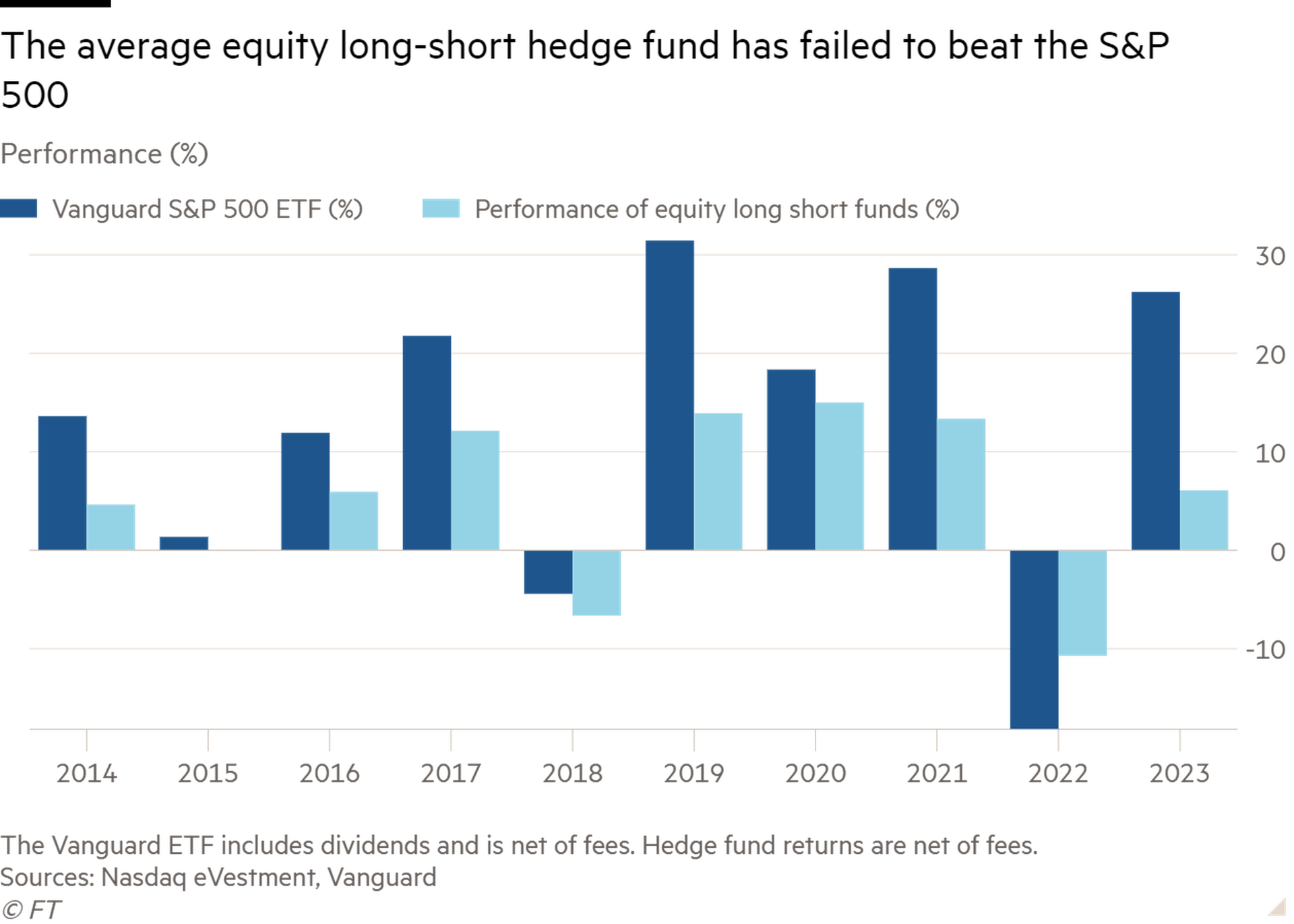

So-called equity long-short funds, which try to buy stocks likely to do well and bet against names set to perform poorly, have underperformed the US stock market in nine out of the past 10 years, according to Nasdaq eVestment, after failing to adapt to markets largely dominated by central banks.

The poor performance and outflows mark a fall from grace for a strategy known for its star stockpickers such as Tiger Management’s Julian Robertson, GLG’s Pierre Lagrange and Egerton’s John Armitage.

“Ten years ago people used to talk about the great equity stockpickers,” said Donald Pepper, the co-chief executive of hedge fund firm Trium, which manages around $1.7bn.

“You still have some rock stars like [TCI’s] Chris Hohn, but there just aren’t many of him around anymore.”

Pioneered in 1949 by investor Alfred Winslow Jones — seen as the world’s first hedge fund manager — equity long-short funds were designed to “hedge” against overall market fluctuations through their bets on both winning and losing stocks.

The strategy made double-digit returns in almost every year of the 1990s bull market, according to data group HFR, with many funds then profiting by shorting wildly overvalued dotcom groups in the ensuing bust. During the global financial crisis, funds such as Lansdowne Partners made millions betting against doomed UK lender Northern Rock.

But since then many funds have struggled, coming unstuck in markets dominated by central bank bond-buying and low interest rates. In the meantime, they have badly lagged cheap index tracker funds that have reaped huge gains from the bull market.

An investor who put $100 into an equity long-short hedge fund 10 years ago would now on average have $163, according a Financial Times analysis of figures provided by Nasdaq eVestment. Had they invested in Vanguard’s S&P 500 tracker with dividends reinvested they would have $310.

“You don’t need your hedge funds to beat the S&P every year, but you do want them to beat it over time, for instance over the past decade,” said a pension fund adviser who allocates billions of dollars to hedge funds.

Big-name funds have suffered. Some of the so-called Tiger cubs — managers who trace their roots back to Robertson’s firm — were among those hard hit in 2022’s market sell-off, including Chase Coleman’s once- high-flying Tiger Global and Lee Ainslie’s Maverick Capital.

In October the FT highlighted billions of dollars of outflows from London-based hedge fund Pelham Capital, run by former Lansdowne portfolio manager Ross Turner, and it 2022 the FT revealed Roderick Jack and Marcel Jongen’s Adelphi Capital would return capital and become a family office.

When Lansdowne shut its flagship Developed Markets equity fund in 2020, after admitting it had become hard to find stocks to short, many saw it as a sign of a deep malaise in the sector.

Long-short managers complained for years that ultra-low interest rates allowed weaker companies — which would previously have been excellent targets to short — to stumble on for longer and, in some cases, for their share prices to soar. That, they said, made it harder for them to profit.

But a sharp rise in interest rates over the past two years has failed to revive the strategy’s fortunes. After large losses in 2022’s downturn, funds were meant to have their breakout year last year as higher rates sifted stronger companies from weaker firms. But funds gained 6.1 per cent on average, compared with the S&P 500’s 26.3 per cent gain.

Adam Singleton, chief investment officer of external alpha at Man Solutions, which invests in other hedge funds, said low volatility and last year’s bull market made it hard for long-short managers to prove themselves.

“Higher interest rates should lead to more good companies succeeding and bad companies failing, but I think markets were very focused on what policymakers like the [US Federal Reserve] would do.”

After more than a decade of excuses, investors are losing patience. Richard Byworth, managing partner at Syz Capital, said his portfolios have not invested in equity long-short funds for close to two years.

“With high fees, long-short managers are just not delivering performance anywhere near a level that would justify a position in our portfolio,” he said. “It is that simple.”

After 23 consecutive months of investor withdrawals, assets in equity long-short funds are down to $723bn, below levels five years ago, according to Nasdaq eVestment. Some of this has flowed to multi-manager hedge funds, which spread clients’ money over a range of strategies including long-short equity. Such funds invest heavily in risk management and are far less affected by the performance of a star stockpicker.

Not everyone is downbeat. There are early signs that shorting is finally becoming “more fruitful” as higher rates hit poor-quality companies, said one executive, while some allocators such as Kier Boley, co-head of alternative investment solutions at Swiss allocator UBP, think funds will profit as the market’s attention switches back to company fundamentals.

“I am bullish on the prospects for long-short strategies,” said Mario Unali, a portfolio manager at investment firm Kairos. “We will see long-short funds likely roar back to pre-2008 levels.”

But an executive at one top long-short fund was less optimistic, saying a widely anticipated fall in global interest rates would hurt the sector.

“Which hedge fund has ever said that the next decade won’t be great [for their particular strategy]?” he said. “[But] long-short hedge funds will continue to dwindle if rates go back down to zero.”

Additional reporting by Laurence Fletcher