Uğur Şahin arrives at BioNTech’s headquarters in the German city of Mainz on the same battered bicycle he has been riding for 20 years. Developing the best-selling Covid-19 vaccine may have transformed BioNTech’s founders into billionaires, but the chief executive of the biotech business has resisted making changes in his personal life.

Şahin and his wife, chief medical officer Özlem Türeci, set up BioNTech in 2008 to create a toolbox to transform the treatment of cancer. Since finding fame, their vision has not shifted. When practising as doctors, the pair had become frustrated at the gap between the cancer drugs available on the wards — and what they believed was scientifically possible.

So, while the mRNA vaccine they developed with the American pharmaceuticals company Pfizer has saved millions of lives and brought economies around the world back to life, it was also, in some ways, a side hustle. BioNTech “is a cancer company that was able to drop everything they were doing to create a Covid vaccine,” says Akash Tewari, an analyst at Jefferies.

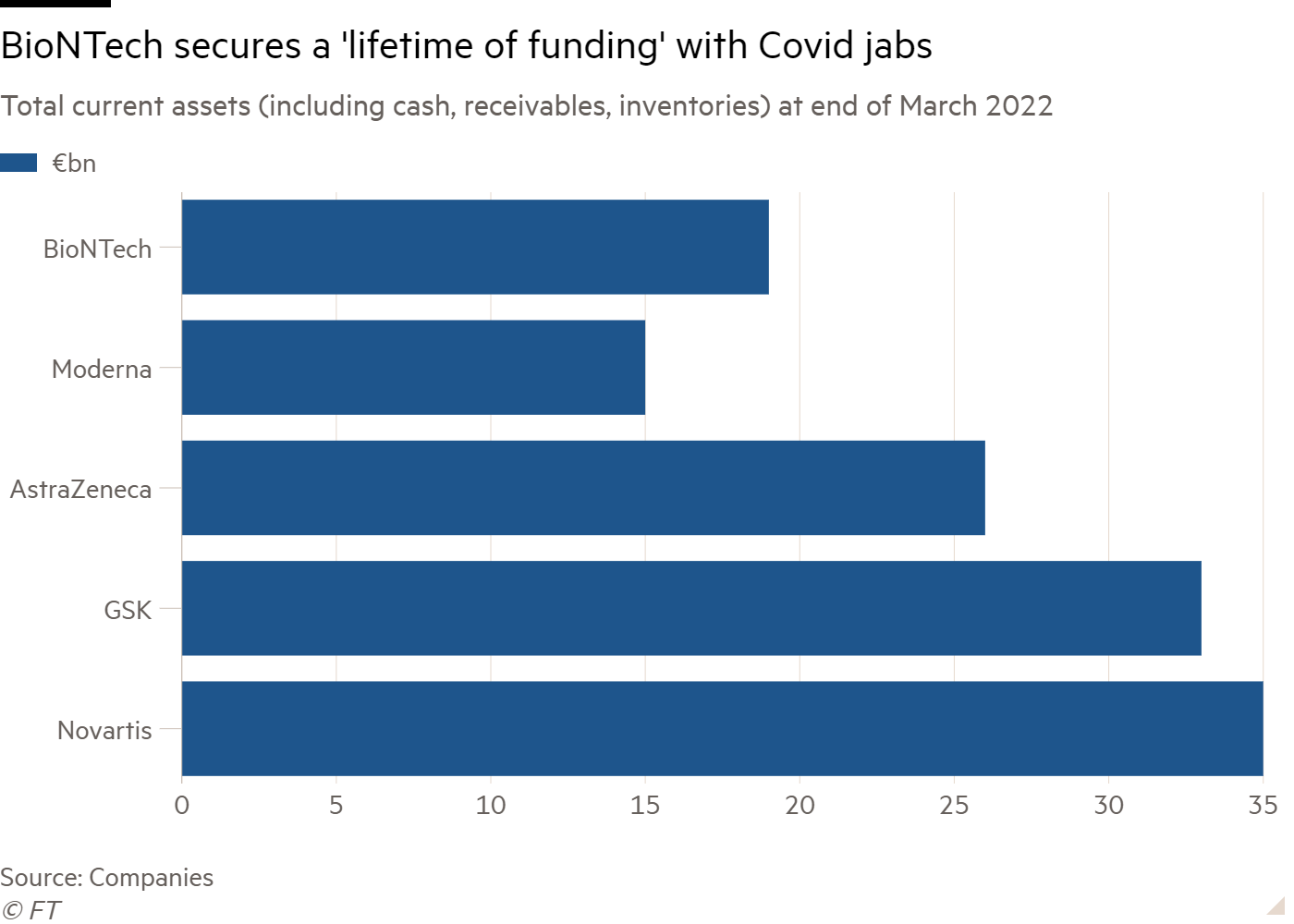

The decision to do so has brought an unprecedented windfall of cash to the company, which is now sitting on assets of €19bn, with billions more in revenue expected. That amount equates to “a lifetime of funding”, says Suzanne van Voorthuizen, co-head of life sciences securities at Dutch bank Kempen & Co.

While some billionaires use their wealth to buy newspapers or fund extraterrestrial adventures, Şahin and Türeci will use theirs to fuel their ambitious — though still nascent — plans in oncology. They are doubling down on a hope that Şahin admits once sounded like science fiction: to be able to tailor drugs to each patient’s cancer.

The company recently took steps in the right direction with two early stage trials showing promising data, one in pancreatic cancer and the other targeting solid tumours including ovarian and testicular cancer.

Success would mean a new journey: reimagining the whole pharmaceutical industry.

“We had this idea to develop technologies dedicated to really saving every single individual patient,” says Şahin. “Because every patient is different, and you can’t just take something off the shelf.”

The Covid cash

Şahin wheels his bike around the perimeter of a huge hole on the plot of the company’s site — the foundation for a new 20,000 square foot building. Across from his office, a three-storey temporary lab in portacabins has popped up to press on with the mission right away: this year research and development spending at BioNTech is doubling to €1.5bn.

Dropping his helmet in his office and donning a white coat, Şahin heads to the lab. Inside, a machine synthesises the DNA templates used to create messengerRNA, the technology BioNTech has helped to pioneer.

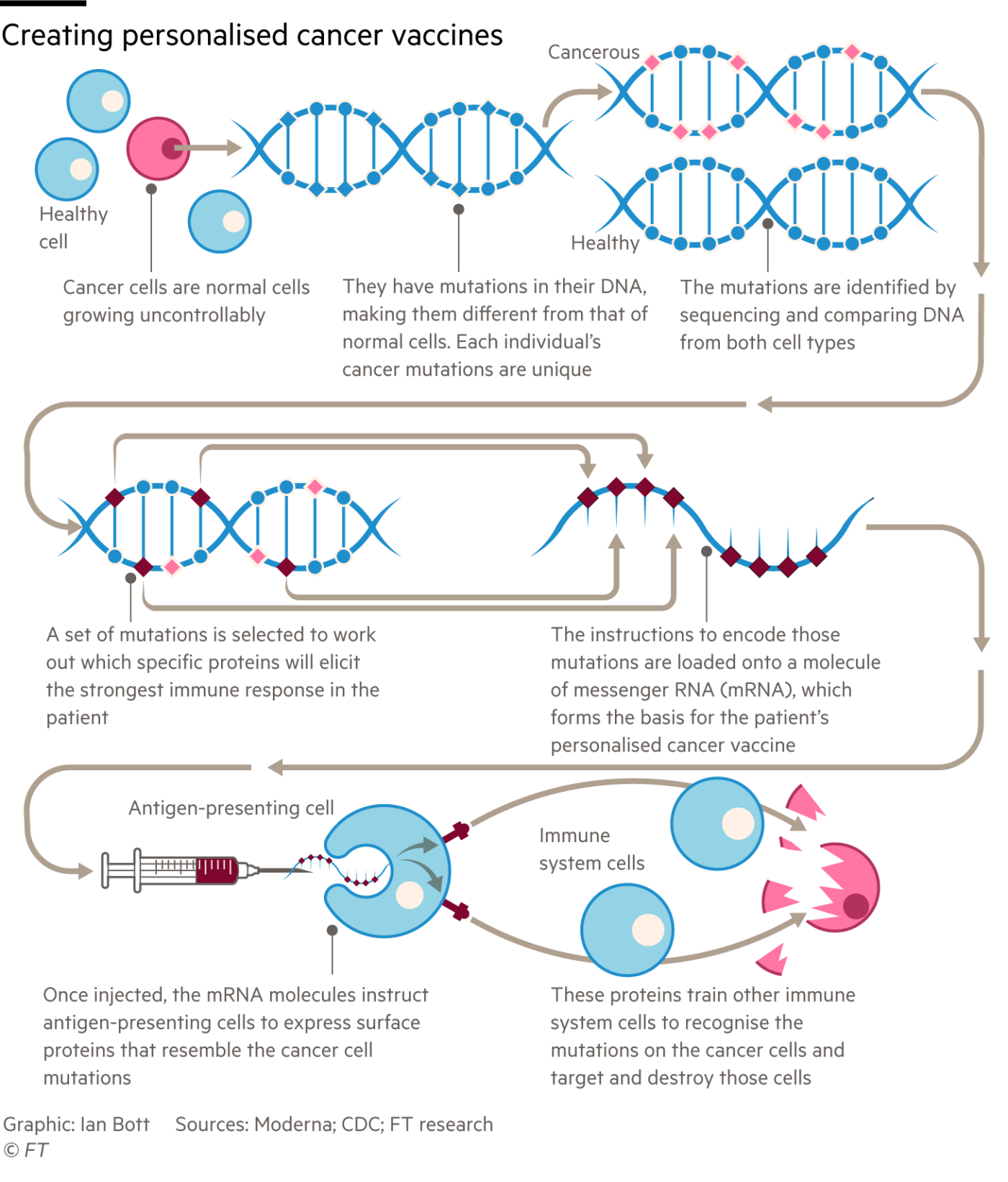

The mRNA acts as a set of instructions to cells, telling them to build certain proteins. The response to the pandemic proved for the first time that the technology could be used to create a highly effective vaccine: mRNA was deployed in a vaccine to help the immune system recognise and fight intruders such as the coronavirus Sars CoV-2. Next, BioNTech wants to use the code to prompt the body’s defences to tackle a tumour.

Yet, unlike its American rival Moderna, which is focused on how to deploy mRNA across a range of infectious diseases and other conditions, BioNTech wants to use mRNA to tackle cancer, working in combination with other therapies. Şahin and Türeci believe the best hopes of a cure will come from combining different treatments, including cell therapies, antibodies and other ways of modulating the immune system.

Before the pandemic, the company was a little known player in the $1.2tn global pharmaceuticals market that is dominated by long-established companies pursuing many disease areas at once. In its 2019 initial public offering, BioNTech struggled to get investors excited, raising just $150mn; two years later it had become the most promising biotech in Europe.

Matthias Kromayer, a managing partner at MiG Capital, who was a founding investor in BioNTech, says when he invested he didn’t even believe in the potential of mRNA. He gave the baby BioNTech money because the founders seemed to understand how technology would change healthcare, he says. “BioNTech isn’t just a biotech company. It is a multi-tech company and has been from the beginning . . . Ugur is always thinking 10 years ahead.”

In April, BioNTech unveiled results of a study that combined mRNA with CAR-T-cell therapy to reprogramme a patient’s immune system. CAR-T is a complex treatment that involves collecting and modifying a patient’s immune cells to fight their cancer. So far, it has only worked in blood cancers. But BioNTech scientists created an mRNA booster that expanded the number of immune cells and improved their ability to kill a solid tumour, making it useful in a far larger range of cancers.

Brad Loncar, a biotech investor who runs a fund focused on cancer, declared it “borderline revolutionary”. “It is so interesting that it has the entire field rethinking how to go after solid tumours,” he says.

BioNTech’s strategy is to invest in many different technologies at once. Şahin uses the analogy of a smartphone that becomes more useful as you discover its many functions. “You understand it is not just a smartphone, it is a calculator, it allows you to do anything,” he said. “Based on the powerful platforms that we are developing, we believe that we will be able to provide a lot of different solutions for many diseases.”

Broadly speaking, the BioNTech founders see themselves as engineers of the immune system. Beyond cancer and infectious diseases, where the company continues to partner with Pfizer on vaccines, they also plan to tackle autoimmune conditions and regenerative medicine, which restores damaged or diseased cells. In total, the company is already running 19 early stage trials and 12 pre-clinical programmes.

Their newly bulging pockets permit such largesse, says one healthcare banker. A more cash-strapped company would have to be more selective and risk “throwing a great technology in the bin”. At the end of March, BioNTech’s assets were more than €19bn, surpassing even Moderna’s €16bn, and more than half that of large European pharma companies GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca and Novartis.

Cancer trials are expensive, especially if a company has to first buy the drug it wishes to combine with its treatment. And personalised products such as CAR-T have proven difficult to market in a global healthcare system that is more familiar with buying drugs off the shelf such as consumer goods.

With valuations of biotech companies dropping this year, Gareth Powell, a healthcare fund manager at Polar Capital, says BioNTech is lucky it can fund so many programmes. “If they didn’t have the Covid cash . . . I would imagine they would be under severe pressure,” he says. “The capital markets just wouldn’t be there for them to do this stuff.”

‘Money doesn’t grow on trees’

Bryan Garnier & Co was part of a team of banks that helped take first Moderna and then BioNTech, public. Pierre Kiecolt-Wahl, co-head of equity capital markets at the French bank, says Moderna took a more incremental approach than BioNTech’s, focusing first on infectious diseases, where it hoped to show signs of success quickly that could persuade investors to put in more funds.

“Moderna knew money doesn’t grow on trees,” he says. By contrast, he says Şahin and Türeci were more confident that they had data to fight cancer.

But even though it now has substantial financial resources, long-term success is not guaranteed. Loncar says it may yet turn out that mRNA doesn’t really work for cancer. “There’s a non-zero per cent chance that mRNA may completely strike out in cancer,” he says. “If that happens, BioNTech is going to feel it a lot harder than Moderna will.”

Oncology is far trickier than creating vaccines — Tewari, the Jefferies analyst, describes it as “scientifically byzantine” — and it is a hypercompetitive field, with almost every major pharmaceutical company scouring for treatments for the same conditions.

BioNTech’s most advanced clinical oncology programme is for cancer vaccines. Unlike regular vaccines, they do not prevent the recipient from developing cancer, but are used as treatments to prompt the immune system to destroy mutated cells. In phase 2 trials, it has two FixVac programmes, where the vaccines are not personalised, and two where they are.

Hopes for creating cancer vaccines have been dashed many times before. “It is a concept that has been around for decades. But there has been failure, after failure, after failure,” says Loncar.

He says one problem could be that therapies are being deployed too late. New therapies are usually tried first in patients who have not responded to previous drugs and usually have later stage cancer, but he believes they might work better at an earlier stage, when the patient’s immune system is more robust.

Şahin counters that BioNTech has overcome a number of “critical hurdles” and that its early data shows its mRNA cancer vaccines are eliciting immune responses several hundred times stronger than were previously reported for conventional cancer vaccines.

The company is also doing trials in earlier stage cancers, and is particularly interested in giving the vaccines just after patients have had surgery to remove the primary tumour. In a phase 1 trial presented this month, the company showed positive results treating pancreatic cancer patients shortly after surgery.

But as well as the scientific uncertainty, BioNTech will face practical challenges as it tries to disrupt the pharmaceutical business. The company will have to push regulators to adapt to individualised therapies that break the mould of conventional clinical trials. While such trials usually take several years and lead to an approved product that never changes, the founders want to be able to update their medicines — like an iPhone — as new data improves algorithms that predict the best way to target a tumour.

Türeci says the company has to take the “smallest steps” with “conservative” regulators whenever they enter new territory. “The problem with the way medicines are developed is that, at that time when you have something you can approve for patients and bring it to the market, the technology is already outdated [by] several years,” she says.

The ‘smallest steps’

While BioNTech’s has no need to beg investors for more capital, the company will still have to navigate expectations of shareholders who bought it as a Covid stock. Shares in BioNTech have fallen by about 20 per cent in the past year, after some investors sold in anticipation that sales of the Covid vaccine would slow. But the stock is still up more than fourfold since March 2020, when the company first announced it was developing a shot with Pfizer.

Loncar, the cancer-specialist investor, does not own BioNTech primarily because it still trades as a Covid stock. He believes shareholders may be in for a surprise. “Investors have been really spoiled by how quickly the Covid-19 vaccines succeeded and how well they did. That’s not normally how drug development goes,” he says. “One thing I worry about is they have a shareholder base today that expects them to succeed in non-Covid things tomorrow.”

Şahin tries to be sanguine about the company’s stock — he says he looks the price up about once a week, far less often than he checks medical journal sites. And he stresses that the company has always been clear with investors about its true vision: “We can’t guarantee to them what is going to happen in the next Covid season. This is more dependent on what’s happening in the world and how the virus is evolving, and less dependent on our competencies.”

Still he was surprised recently when the share price rose as investors anticipated the company would create a vaccine for monkeypox. (BioNTech has not started work on a jab for the spreading disease. Şahin says they are “preparing ourselves to be prepared” to do so, but it does not look like a global challenge yet.)

Some investors are asking whether BioNTech can handle quite so much cash — and take on so many challenges at once.

While the company has decided to use the vast majority of its vaccine proceeds for internal investment, with just a couple of small bolt-on acquisitions, it did announce plans to return almost €2bn to shareholders in a buyback and dividend. This also divided shareholder opinion, because it is so unusual for a biotech with many programmes in early stage development to cough up cash. “It was a terrible idea,” says Powell at Polar Capital. “It’s such a waste of money.”

But analysts say that most long-term investors trust the founders who delivered the Covid vaccine at such scale and speed. Van Voorthuizen at Kempen says they are particularly “diligent” about structuring their trials so that they give solid answers to specific questions. “They will stop [a trial] if it doesn’t work. They are not depending on one or other programmes to make or break the company,” she says.

The healthcare banker believes BioNTech is “by far the most exciting biotech in Europe”, adding that there are no founders more inspirational than Şahin and Türeci. “They are so insanely smart and they work so damn hard,” he says.

Türeci describes how Şahin can suck up information, rapidly reading dozens of papers on a new condition. “It’s sort of something like machine learning what he does,” she jokes. “In a weekend, the entire history of science on this specific topic.”

Governments from around the world are calling for advice for birthing their own versions of BioNTech, Türeci says. But, just as the company surprised the world in 2020 by navigating the uncharted waters of mRNA vaccine development, Türeci says they are once again heading into “unknown territory”. And this time, success is not likely to happen at lightspeed.