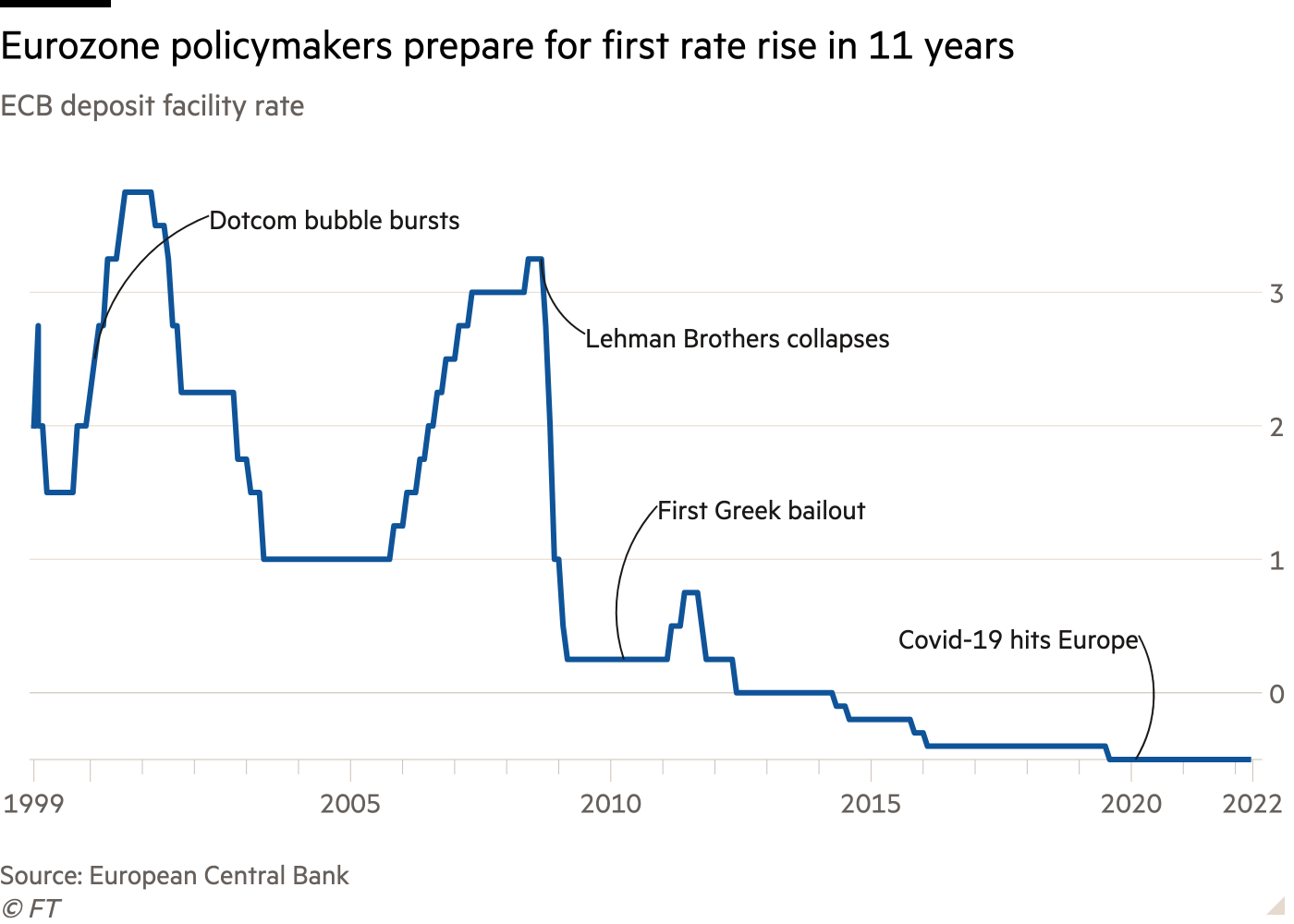

The last time the European Central Bank raised interest rates in 2011 it was forced to reverse the move within months as the eurozone was plunged into a wrenching debt crisis. The market panic that followed only subsided after Mario Draghi, then head of the ECB, declared it would do “whatever it takes” to save the euro.

Fears of a similar outcome are front of mind for many as current president Christine Lagarde prepares the ECB’s first rate rise in 11 years. The move, to be announced on Thursday, will come alongside a new bond-buying plan that the central bank hopes will prevent rising borrowing costs from sparking another eurozone debt meltdown.

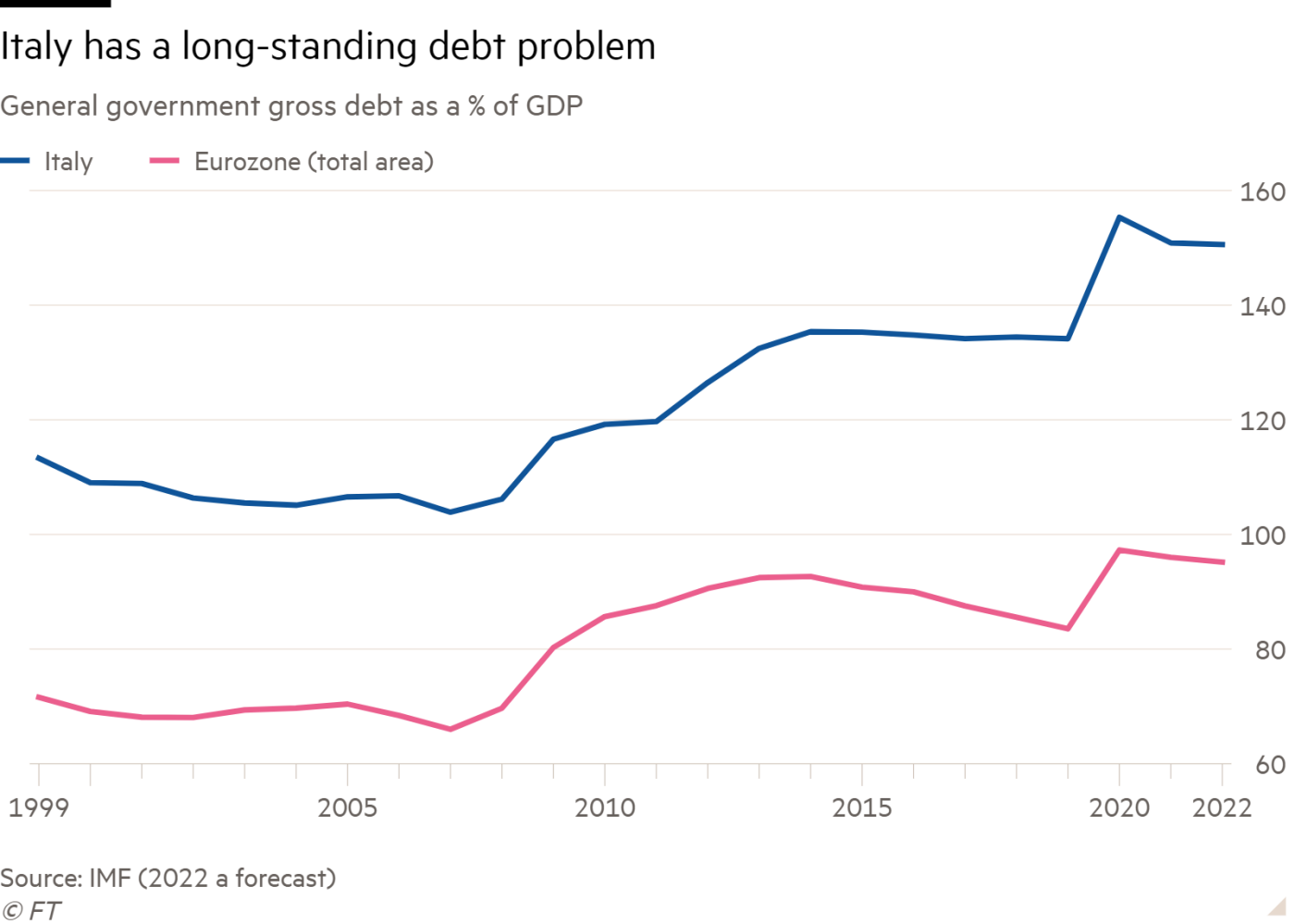

Draghi, who left the ECB in 2019 and became the Italian prime minister last year, seems bound to play a pivotal role once more as he prepares to address parliament in Rome on Wednesday, only days after his ruling coalition splintered. This has fuelled speculation about an early Italian election this year, which could shake investors’ confidence in the country’s ability to manage its swollen public debt that now stands at more than 150 per cent of gross domestic product.

As well as political upheaval in Italy, economists also worry about a growing energy crisis in Germany, where officials are nervously waiting to find out if Russia will turn the gas back on this Thursday after a scheduled 10-day maintenance period for one of its main pipelines to Europe. If the gas does not flow or if there are further delays in winter, several EU countries that rely on it are set to impose energy rationing, starting with heavy industrial users, which is likely to trigger a severe economic downturn across the bloc.

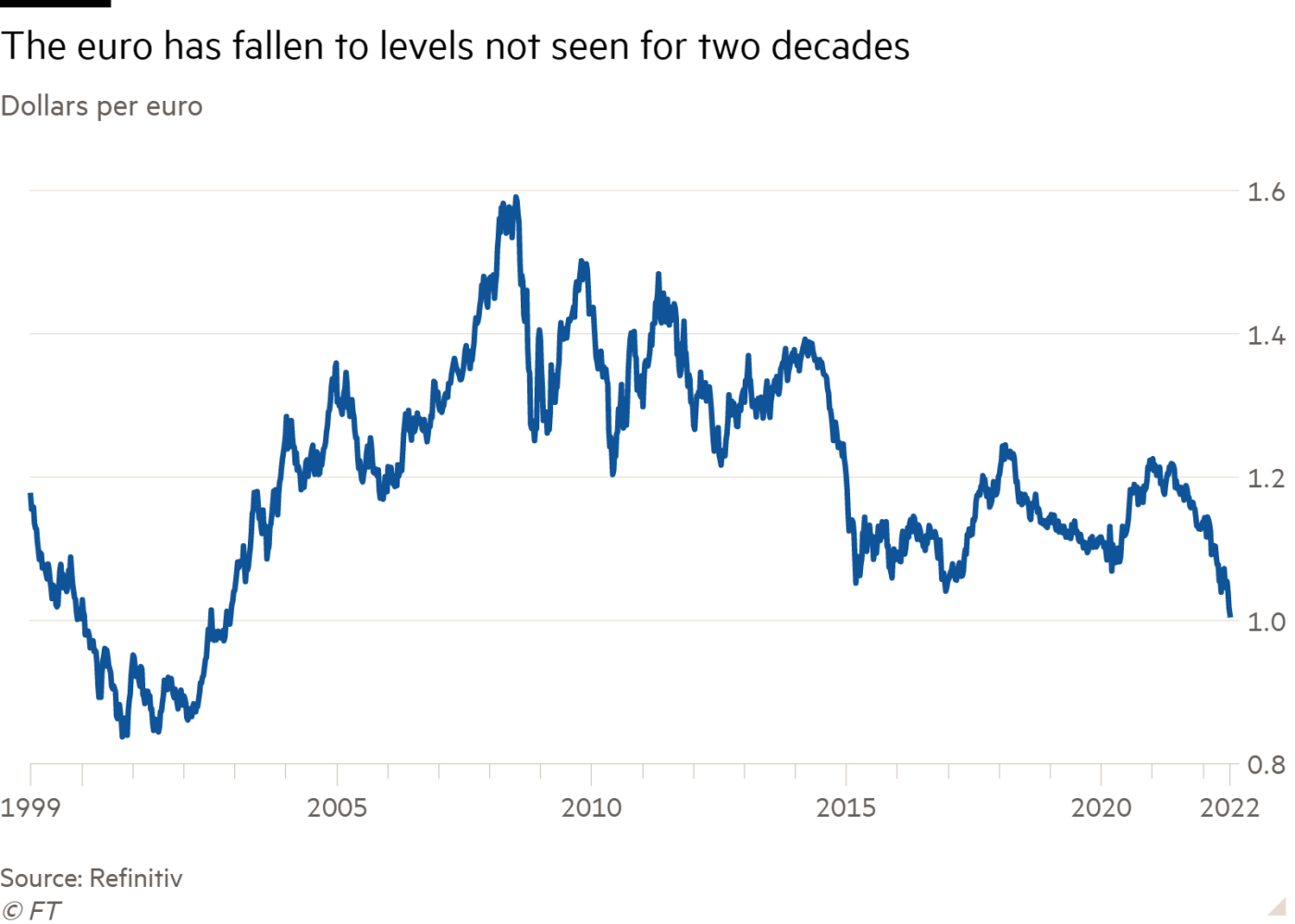

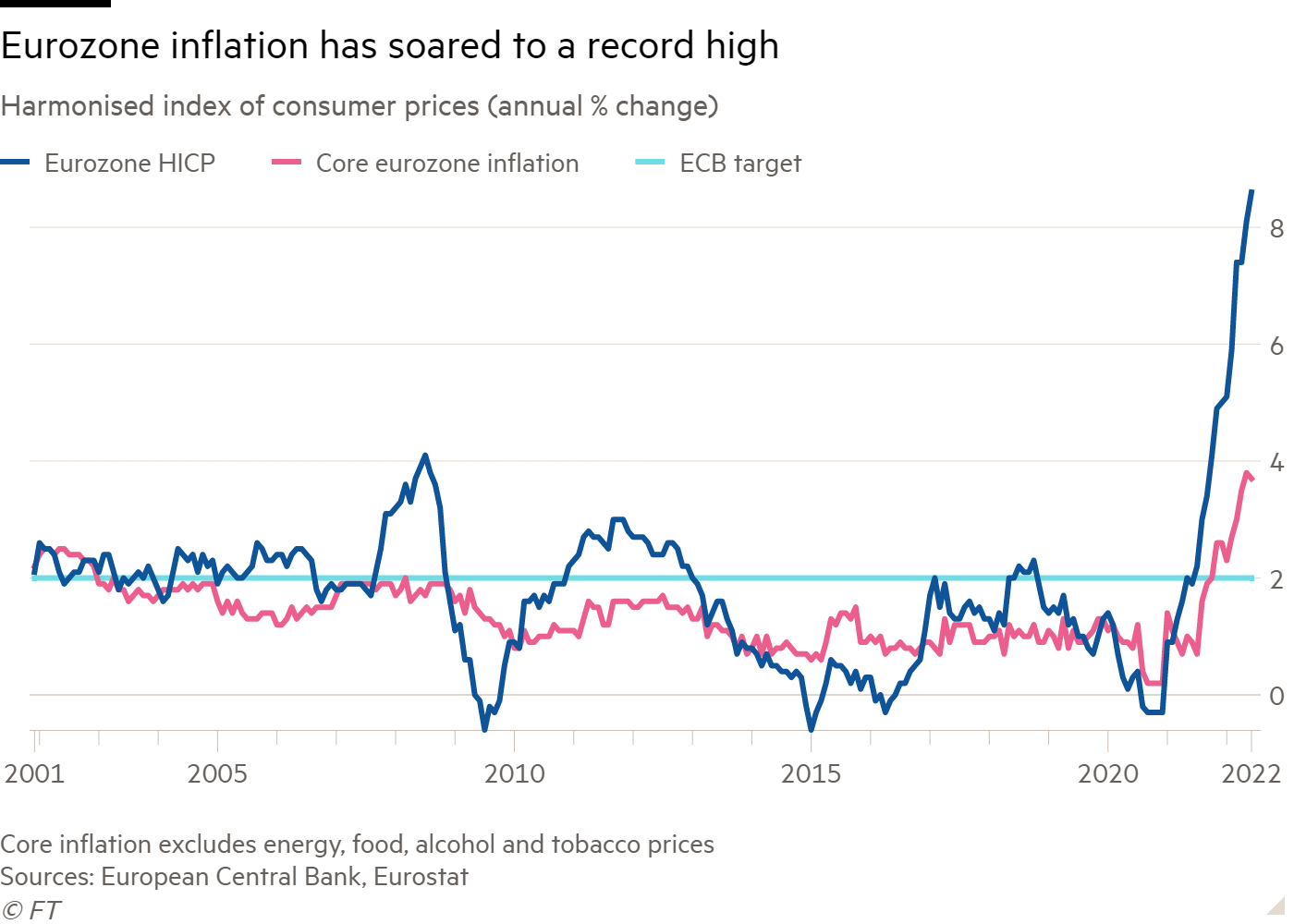

The worsening outlook is reflected in last week’s sharp fall in the euro below the value of the US dollar for the first time in 20 years. Yet the ECB has little choice but to start raising rates after inflation in the bloc surged to a record high of 8.6 per cent in the year to June, more than quadruple its target.

“The risk ahead of us is that because of the energy crisis, the euro area could end up in recession, while at the same time the ECB will have to keep raising interest rates if inflation does not come down,” says Maria Demertzis, deputy head of the Brussels-based Bruegel think-tank. “It is an almost impossible situation.”

‘Too slow and too late’

The ECB is grappling with more complex challenges than most major central banks. The eurozone is bearing the brunt of the fallout from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The war is driving up energy and food prices and fuelling political instability, while the risk of a fresh eurozone debt crisis is never far away due to the incomplete nature of its monetary union with different countries having separate budgets and bond markets.

In these volatile circumstances, Lagarde has said the central bank intends to normalise policy “gradually” starting with a quarter point rise in its deposit rate to minus 0.25 per cent on Thursday ahead of a bigger rise above zero in September if price growth remains high.

The ECB has acted more cautiously than the Federal Reserve, which has already raised US rates three times and is next week expected to raise them again by at least three-quarters of a percentage point. The IMF said that over the past year 75 of the 100 central banks it tracks have raised rates on average almost four times each, by 3 percentage points in emerging markets and 1.7 points in advanced economies.

Many believe the ECB is being too timid to curb inflation, which hit double-digit figures in nine out of the 19 eurozone countries in June. “The very gradual and cautious normalisation process the ECB started at the end of last year has simply been too slow and too late,” says Carsten Brzeski, head of macro research at Dutch bank ING.

Some members of the ECB’s rate-setting governing council — notably those in Baltic countries where inflation is close to 20 per cent — have broken ranks to call for a more aggressive half-point rate rise on Thursday.

“It is like antibiotics, it doesn’t help if you take them in September if you are ill now,” says one of the more hawkish ECB council members. “Interest rates are our medicine and the timing and size of the dosage are of utmost importance.”

Up to now, the eurozone economy has been relatively resilient, with retail sales and industrial production remaining above last year’s levels, while the lifting of Covid-19 restrictions has boosted summer travel and tourism.

But economists expect high prices to erode the spending power of European households and weigh on industrial output as companies reduce production.

“If you are a company and gas is an essential input for production, you are probably going to [have started to] produce less already in anticipation of possible supply disruptions,” says Spyros Andreopoulos, senior European economist at French bank BNP Paribas. “We are already seeing signs of this starting to happen.”

Economists at Germany’s Deutsche Bank estimate the skyrocketing price of imported energy and food will deliver a €400bn negative hit to the eurozone’s balance of trade this year. This is already draining confidence among consumers and businesses, which points to a likely downturn later this year, especially as the US and Chinese economies are already slowing sharply.

But the single biggest thing keeping senior ECB officials awake at night is the fear that Russia is weaponising its energy exports to press for an advantage in its invasion of Ukraine by increasing the economic pain for Europe.

“The dependency of European countries — and the euro area is a case in point — on external supplies from foes, has had a major impact on prices,” Lagarde said in June. “That could contribute to inflation directly — if it leads to further rises in energy costs — or indirectly, if a higher level of energy prices makes some production uneconomic and leads to a durable loss of economic capacity.”

Sven Jari Stehn, chief European economist at US investment bank Goldman Sachs, says eurozone inflation is likely to peak above 10 per cent in September. But if Russian gas flows stopped completely, he warns “the risks are skewed towards a sharp contraction and even higher inflation”, adding the eurozone economy would keep shrinking until the second quarter of next year in these circumstances.

“It is a nightmare scenario for economic policymakers,” says Lars Feld, an economics professor at the Albert Ludwigs University of Freiburg, who advises the German finance minister. “It is more difficult than in the 2012 debt crisis, when we had a clear choice between monetary policy or fiscal policy solutions, but now both are much less clear.”

Living with the ghosts of the debt crisis

As long as inflation continues to rise, the ECB is expected to keep raising rates even if the economy starts to nosedive, while higher borrowing costs will make it harder for governments to spend more on shielding their citizens from the soaring cost of living. This is fuelling political tensions across Europe.

Public anger over surging energy and food prices played a key role in the fracturing of Draghi’s ruling coalition in Italy, which resulted in him offering his resignation — only to have it turned down by the president. High inflation also eroded support for French president Emmanuel Macron and contributed to his failure to win a parliamentary majority in elections in June.

“I fear political instability in Europe, in Italy and, of course, in France,” says Vítor Constâncio, former vice-president of the ECB who is now economics professor at the University of Navarra in Madrid. “If Macron has problems approving the budget next year there could be elections in France and the prospect of an Italian election is also a complicating factor, no doubt.”

Borrowing costs are already rising faster for heavily indebted southern European countries, such as Italy, than for some of their more fiscally solid northern counterparts, recalling the demons of the sovereign debt crisis that nearly ripped the eurozone apart a decade ago.

This is an uncomfortable reminder for the ECB that, unlike the Fed or the Bank of England, it sets monetary policy for 19 different countries, each with its own budget and — crucially — bond market. That leaves the single currency vulnerable to a divergence in borrowing costs between countries which can test the sustainability of national debt levels.

“Of course you always have this general risk of a crisis in the periphery of the euro area playing out in the background,” says Dirk Schumacher, head of Europe macro research at French bank Natixis. “It is something the Fed doesn’t have to deal with.”

In response, the ECB is expected to announce that it will tackle any unwarranted divergence in a country’s bond yields by buying its bonds using a new scheme it calls the transmission protection mechanism.

Unlike the yield curve control policy of Japan’s central bank, which is buying as many bonds as needed to cap the country’s borrowing costs at a fixed level, the ECB is unlikely to target a specific bond yield for each nation and will instead use its judgment on when to intervene.

That has sparked worries, particularly in more frugal countries such as Germany and the Netherlands, that the ECB will encourage fiscal profligacy among member states and stray into “monetary financing” of governments — the printing of money by a central bank to prop up a country’s budget — which is against the EU treaty.

“Distinguishing what is political risk from market speculation empirically is impossible,” says Feld, the former chair of Germany’s council of economic experts. “The market pricing will have some disciplining effect on political decisions and we should let it work.”

Watching for market disruptions

The mounting anxiety in EU capitals over how best to respond to the punishing combination of rising prices and slumping growth is clear. While not forecasting a recession, the European Commission last week downgraded growth estimates and sharply increased predictions for inflation, which is now tipped to hit 7.6 per cent in the euro area this year and remain at twice the ECB’s 2 per cent target in 2023.

Draft commission proposals, due for release this week, would limit energy usage in public buildings, as it scrambles for ways of conserving gas given the threats from Moscow.

Officials are blunt about the economic headwinds facing Europe. Klaus Regling, head of the European Stability Mechanism bailout fund, last week warned that while the economy and consumers were under “massive strain”, markets are facing greater volatility given the combination of higher inflation and interest rates — something many traders have never experienced in their professional lives.

That does not mean we are facing a new “euro crisis”, insists Regling — a sentiment echoed by Paschal Donohoe, the eurogroup president, who has repeatedly stressed the stronger institutional set-up that the euro area enjoys today compared with a decade ago.

Nevertheless, the dangers of a sudden loss of market confidence are hanging heavily over officials’ planning — with Italy front and centre of their concerns.

The eurogroup last week discussed the creation of an informal task force of officials to monitor the markets during the summer break — a period in which low liquidity and thinly staffed trading floors can give rise to disruptive movements in bond yields and stock markets. The group will scan for emerging market hazards and have the power to convene policymakers if trouble erupts, according to people familiar with the plans.

The search for closer co-ordination between institutions and member states speaks to a broader concern among finance ministries — namely the risk of disjointed or contradictory action by different member states that ends up eroding, rather than shoring up, market confidence.

Emerging from a meeting in Brussels last Tuesday, Sigrid Kaag, the Dutch finance minister, stressed the need for unity among the currency union’s capitals, warning: “Everyone is struggling with the same issues, and if a recession is looming . . . I think we need to meet and converge around the same choices”.

The 19 eurozone finance ministers say they have already agreed not to boost demand via extra borrowing next year, to ensure they don’t further stoke inflationary pressures.

Holding a clear agreed line will, however, be much easier said than done. Italy is the main focus of member states’ concerns, given the risk that Rome will fall behind on its reform commitments or fail to keep a tight grip on public borrowing.

Giuseppe Conte, the head of the Five Star Movement, last week withdrew its support from Draghi’s national unity government, throwing the ruling coalition into chaos. Conte accused the prime minister of doing too little to help families clobbered by soaring energy and food prices.

If the government were to collapse it would raise doubts about Rome’s ability to pass a budget in November, fanning fears in northern capitals that Italy will once again emerge as a dangerous weak spot in the euro area’s armour.

Asked on Thursday about the situation in Rome, Paolo Gentiloni, the European economy commissioner, stressed the importance of not adding political tremors given the febrile global situation. “In these troubled waters — war, high inflation, energy risks, geopolitical tensions — stability is a value in itself. Now is the time for sticking together, for cohesion,” he said.

After the Covid-19 pandemic hit in 2020, plunging much of Europe into a record postwar recession, Lagarde said there were “no limits” to the central bank’s commitment to the euro. That pledge may be about to be tested again.